Women bear it all? Assessing heterogeneity in water burden and its effect on education and labor market participation across gender in Malawi

Guest post by the Princeton University Economic Development Organization

The Princeton University Economic Development Organization (PUEDO) is a group of Princeton University students who partner with organizations around the world dedicated to economic development. We leverage economic research methods to understand how policy impacts people in order to support the missions of our partner organizations. PUEDO is honoured to have a longstanding relationship with Pump Aid in support of their mission to end water poverty in Malawi.

This post was written by Sofia Arora, Siling Song, and Aidan Cusack. We are undergraduate students studying Economics at Princeton University and are interested in applying quantitative methods to issues in development economics, particularly pertaining to health and gender.

In this research brief, we seek to understand how the burden of water collection impacts women and girls’ opportunities for education and work in Malawi. We find that the water burden seems to fall predominantly on Malawian women, reducing their odds of accessing education during adolescence and of participation in full-time employment in adulthood, while the relationships were insignificant for men.

Improving access to water and reducing the labour burden on women is a key part of efforts to reduce gender inequality by increasing education access for young girls and labour force participation for women in Malawi.

Introduction

Lack of access to clean water sources is a pressing problem for many Malawian households. Despite its landlocked location in southeastern Africa, Malawi is a water rich country with 20% of its land covered in surface water (World Bank, 2025). However, much of this clean water does not reach the 81% of Malawians who live in rural areas because of the lack of infrastructure, creating a disparity in water access between its urban and rural regions (World Bank, 2024). 37% of rural households in Malawi spend 30 minutes or more fetching drinking water daily, compared to 13% of urban households (UNICEF, 2020). This leaves about 1 in 4 Malawians without a consistent, clean water source within a 30 minutes’ walk (Cassivi et al., 2020).

Our research aims to understand how this lack of access to clean water impacts educational attainment and labour force participation. We use empirical data from the Malawi Integrated Household Survey for our analysis. We pay special attention to the effects on women and girls, since the responsibility of trekking 30 minutes or even further for clean drinking water typically falls on them. One UN study of 24 countries in sub-Saharan Africa claims that “women who collected water spent 54 minutes [collecting water] on average, while men spent only 6 minutes” (UNICEF, 2016).

Literature Review

Access to safe water is widely recognized as a critical indicator of economic development and poverty reduction. In rural Malawi, where poverty rates are nearly 30 percent higher than in urban areas, empirical evidence demonstrates a significant, though modest, correlation (0.28) between poverty and inadequate water access, highlighting the intertwined nature of these challenges (Mkondiwa et al., 2013). This finding is broadly supported by a cross-national analysis of low- and middle-income economies which show that socioeconomic factors strongly shape water access outcomes; female education and rural population growth emerge as particularly important determinants (Gomez et al., 2019). Notably, higher rates of female primary school completion are consistently associated with better rural water access regardless of income level, underscoring the role of education and gender equity in mitigating water poverty.

The intersection of water access and gender has impacts on individual educational outcomes. An analysis of nine low- and middle- income countries, including Malawi, examined how improved access to water infrastructure impacted women’s labor force participation as well as educational attainment (Koolwal & Van de Walle, 2013). While no effect was observed on women’s labor force participation by improving water access, educational attainment and attendance improved (Koolwal & Van de Walle, 2013). Koolwal and Van de Walle attribute this improvement in attendance to the decreased burden that children, particularly girls, face given their water fetching responsibilities. Aside from time spent water fetching, access to Water, Sanitation, and Health (WASH) facilities has a disproportionate effect on female school attendance. Fleifel and Khalid found that in Malawi, girls without access to clean latrines skipped school at twice the rate of those who have private latrines (Fleifel & Khalid, 2019).

Previous literature has established a relationship between water access and educational attainment. However, the disparate effects of water access on education for men and women remains under-researched. Thus, we sought to fill this gap in the literature by investigating how time spent accessing water affects education, educational attainment and labor force participation, while specifically seeking to quantify how gender affects this relationship.

Data & Methodology

Every three years, the National Statistical Office of Malawi conducts a survey of thousands of households to study long-term trends in poverty, agricultural work, demographics, and socioeconomic characteristics (National Statistical Office, 2020). This panel data surveyed the same 3,104 households in 2010, 2013, 2016, and 2019 to understand trends within individual households over time. This dataset is especially useful for our purposes since its panel structure allows us to apply a fixed effect model that could better address time-invariant confounding variables and improve the accuracy of our estimates. Our research goal is to analyse how the amount of time individuals spend collecting water is related to their education access, attainment, and labour force participation. We especially consider the impact of gender in relation to these variables.

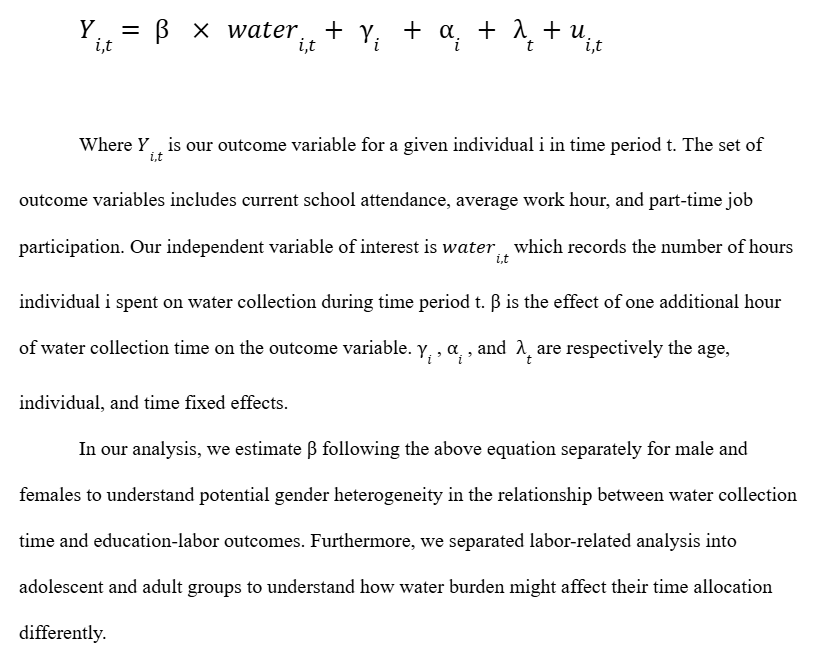

Our estimation strategy follows the following model:

Results & Discussion

Access to Education

We find that a child’s probability of regularly attending school is impacted by both gender and the time they spend collecting water. Girls are less likely than boys to currently attend school regardless of water collection time. While the effect of water collection time alone on the probability of school attendance seems insignificant, we do find that girls become more likely to stop attending school than boys when their water collection burden increases, as shown in columns 1 and 2 of Figure 1. If a family needs a child to trek far to collect water, it is more likely for a girl child to stop attending school in order to do this.

However, we find an insignificant effect of water collection time on markers of educational attainment such as the ability to read or write short messages, speak English or Chichewa, or do basic arithmetic. There is no effect when we consider gender either, perhaps because girls in Malawi actually finish primary school at slightly higher rates than boys, although that trend reverses sharply for secondary school as girls drop out in large numbers (UNESCO, 2024).

In general, it is difficult to make conclusive statements about the effect of water collection time on girls’ educational access and achievement due to the limitations by the nature of survey data. We might have response bias from self-reported values in the surveys, general measurement error, or other unaccounted variables that affect outcomes. We attempt to account for the effect of omitted variables such as an individual’s interest in education using a fixed effects regression, which is presented in Figure 1.

Overall, the empirical evidence does suggest that there is a link between water collection time and decreased school attendance for girls.

Fig. 1: Teen Education and Labour Force Participation: Fixed Effect Model

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| School Attendance (Male) | School Attendance(Female) | Work Hours (Male) | Work Hours (Female) | Part Time Job Participation (Male) | Part Time Job Participation (Female) | |

| Water Hours | -0.00986 | -0.0280** | 0.0106 | 0.0243*** | 0.00941 | 0.0241*** |

| (0.0145) | (0.0123) | (0.0277) | (0.00858) | (0.0124) | (0.00932) | |

| Age FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 4111 | 4348 | 4844 | 5156 | 3954 | 4222 |

Standard errors in parentheses

* p < 0.10, ** p < 0.05, *** p < 0.010

Fig. 2: Adult Education and Labour Force Participation: Fixed Effect Model

| (7) | (8) | (9) | (10) | |

| Work Hrs(Male) | Work Hrs (Female) | Part Time Job Participation (Male) | Part Time Job Participation (Female) | |

| Water Hours | -0.813 | -0.424** | 0.0205 | 0.0225** |

| (1.052) | (0.195) | (0.0314) | (0.00981) | |

| Age FE | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 6158 | 6750 | 5100 | 5558 |

Standard errors in parentheses

* p < 0.10, ** p < 0.05, *** p < 0.01

Labour Force Participation

We also find significant results indicating that longer water collection time for working-age women negatively impacts their hours of paid work per week. An increase of one hour of water collection time per day is associated with a decrease of -.42 hours of working time per week for women. On the other hand, the effect is null for men (Figure 2).

For teenage girls, longer water collection time increases the time they spend working per week. This might mean that water collection responsibilities decrease their likelihood of school attendance as we saw in the previous section, and instead push them into part time or contract work. Water collection time is also positively associated with having a part-time job for children under 12 (Figure 1).

This empirical evidence suggests that when women and girls spend more time per week collecting water for their families, they forgo opportunities for human capital accumulation. Girls and teens sometimes exit the education system due to their household responsibilities and instead enter the labor force. On the other hand, the evidence suggests that some adult women work less outside of the home because of household responsibilities. This is an obstacle to human capital development.

Conclusion & Policy Implications

Our empirical analysis of the data suggests that when school-aged girls in Malawi spend more time collecting water, they are less likely to attend school and more likely to work outside the home, preventing them from pursuing higher education. On the other hand, adult women who spend more time collecting water are less likely to work outside the home, indicating that the burden of their home responsibilities precludes them from other options in the workforce. This suggests that improving access to water and reducing the labour burden on women is a key part of efforts to improve education access for young girls and labour force participation for women in Malawi.

References

Cassivi, A., Tilley, E., Waygood, E. O. D., & Dorea, C. (2020). Trends in access to water and sanitation in Malawi: progress and inequalities (1992–2017). Journal of Water and Health, 18(5), 785–797. https://doi.org/10.2166/wh.2020.069

Fleifel, E., Martin, J., & Khalid, A. (n.d.). Gender Specific Vulnerabilities to Water Insecurity. https://ic-sd.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/eliana-fleifel.pdf

Koolwal, G., & van de Walle, D. (2013). Access to Water, Women’s Work, and Child Outcomes. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 61(2), 369–405. https://doi.org/10.1086/668280

Malawi: Education Country Brief. (2024). Unesco.org. https://www.iicba.unesco.org/en/malawi

Mkondiwa, M., Jumbe, C. B. L., & Wiyo, K. A. (2013). Poverty-Lack of Access to Adequate Safe Water Nexus: Evidence from Rural Malawi. African Development Review, 25(4), 537–550. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8268.12048

National Statistical Office. (2020, December 7). Integrated Household Panel Survey 2010-2013-2016-2019 (Long-Term Panel, 102 EAs) – Malawi. Worldbank.org. https://microdata.worldbank.org/index.php/catalog/3819

World Bank Group. (2024). Malawi Overview. https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/malawi/overview.

World Bank Group. (2024). Rural population – Development Indicators. World Bank Open Data, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.RUR.TOTL.ZS.

UNICEF. (2016, August 29). UNICEF: Collecting water is often a colossal waste of time for women and girls. Unicef.org. https://www.unicef.org/press-releases/unicef-collecting-water-often-colossal-waste-time-women-and-girls

UNICEF. (n.d.). Water, sanitation and hygiene. Www.unicef.org. https://www.unicef.org/malawi/water-sanitation-and-hygiene